Where is Diego Garcia Base?

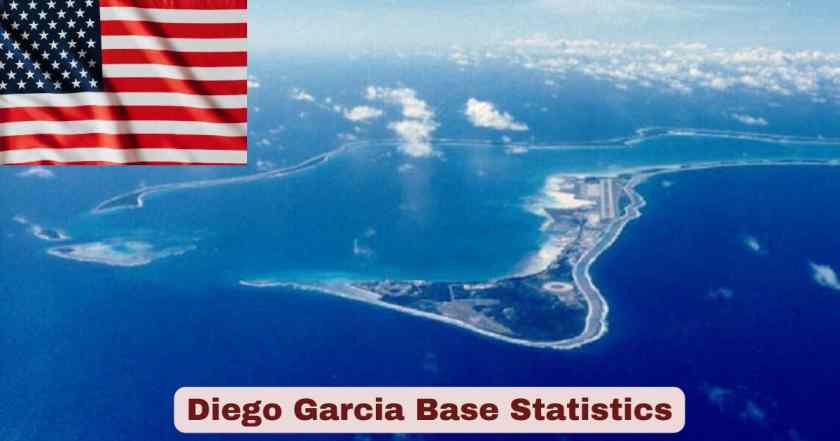

Sitting quietly in the middle of the Indian Ocean, Naval Support Facility (NSF) Diego Garcia has never been more strategically important than it is right now in 2026. The joint US-UK military base, often called the “Footprint of Freedom”, occupies the largest atoll of the Chagos Archipelago and serves as the United States’ only permanent military installation in the Indian Ocean. With rising tensions in the Middle East, an evolving geopolitical rivalry with China, and an ongoing sovereignty controversy between the United Kingdom and Mauritius, Diego Garcia base 2026 statistics tell the story of a facility that punches far above its geographic weight. The base supports a full spectrum of military operations — from deep-space satellite tracking to strategic bomber deployments — all from a coral island measuring just 17 square miles.

The year 2026 brings fresh significance to Diego Garcia, as the United Kingdom’s landmark treaty with Mauritius, signed on May 22, 2025, moves closer to full ratification. Under that deal, the UK secured a 99-year lease on the base while transferring sovereignty of the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius — at an estimated cost of £101 million per year. Meanwhile, satellite imagery from as recently as February 1, 2026, confirms continued heavy US military aircraft activity on the runway. From the base’s physical dimensions and personnel figures to its lease costs and operational history, here is a comprehensive, data-driven look at everything that matters about Diego Garcia base stats in 2026.

Interesting Facts About Diego Garcia Base 2026

| Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Official Designation | Naval Support Facility (NSF) Diego Garcia |

| Nickname | “Footprint of Freedom” / “Fantasy Island” |

| Location | Central Indian Ocean, 7°S, 72°E |

| Part of | British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) / Chagos Archipelago |

| Only US Base in Indian Ocean | Yes — the only permanent US military installation in the Indian Ocean |

| Atoll Shape | V-shaped coral atoll |

| Island Length | Approx. 15 miles (24 km) |

| Maximum Atoll Width | Approx. 7 miles (11 km) |

| Total Land Area | 17 square miles (44 sq km) |

| Distance from Tanzania | 3,535 km (2,197 miles) |

| Distance from Maldives | 726 km (451 miles) |

| Distance from Somalia | 2,984 km (1,854 miles) |

| Operational Since | 1971 (construction); formally established October 1, 1977 |

| GPS Control Station | One of five global GPS control bases operated by the US military |

| Base Nickname History | Named after Spanish/Portuguese explorer Diego Garcia de Moguer (16th century) |

| Chagossians Expelled | Approx. 2,000 people forcibly removed between 1968–1973 |

| First Aircraft Carrier at Base | USS Saratoga (CV-60), 1985 |

| First Women Stationed | March 26, 1982 (Barbara Shuping + 5 others) |

| Sovereign Status as of 2026 | UK ceded to Mauritius (May 2025 treaty); UK retains 99-year operational lease |

| US Lease Expiry (Original) | 2036 (current operational agreement) |

Sources: Wikipedia – Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia; Wikipedia – Diego Garcia; Britannica – Diego Garcia; Naval Technology – NSF Diego Garcia

The facts above lay out just how unique Diego Garcia is as a military installation. There is simply no other base quite like it — a tiny tropical atoll that serves as the lone American military anchor in the Indian Ocean, capable of projecting air and naval power from the coast of East Africa all the way to Southeast Asia. Its nickname “Footprint of Freedom” reflects not just its geography but its symbolic weight in American and British defense planning. The expulsion of approximately 2,000 Chagossians between 1968 and 1973 to build this base remains one of the most controversial chapters in modern colonial history, a wound that the May 2025 UK-Mauritius sovereignty deal has attempted — imperfectly — to address. The fact that Diego Garcia is also one of only five global GPS ground control stations underscores how deeply this single island atoll is woven into the infrastructure of modern global navigation.

What makes these facts even more striking in 2026 is the combination of continued military relevance and unresolved political uncertainty. President Trump’s January 2026 social media post calling the UK’s Chagos deal an “act of GREAT STUPIDITY” thrust the base back into global headlines. Satellite imagery published on February 1, 2026, confirmed at least six military aircraft positioned on the runway — consistent with a pattern of heightened activity observed before and after major Middle East operations. The base is not merely a footnote in US military history; it is an active, operational linchpin whose statistics speak to a facility in constant, high-tempo use.

Diego Garcia Base — Physical Infrastructure Statistics

| Infrastructure Feature | Data / Specification |

|---|---|

| Runway Length | 3,659 meters (12,000 feet) |

| Runway Width | 61 meters (200 feet) |

| Runway Surface | Concrete |

| Runway Designation | 122°/302° (Runway 13/31) |

| IATA Airport Code | NKW |

| ICAO Airport Code | FJDG |

| Aircraft Arresting Systems | BAK-12 (both runway ends) |

| Compatible Aircraft Types | C-130, C-141, C-5, KC-10, C-17, B-1, B-2, B-52, P-8A Poseidon |

| Deep-Water Port | Yes — capable of docking nuclear submarines and aircraft carriers |

| Lagoon Anchorages | 20 deep-water anchorages |

| Fuel Storage Capacity | 1,340,000 barrels (213,000 m³) |

| Number of Separate Commands on Base | 16 |

| Prepositioned Ships (MPSRON 2) | 20 deep-water logistics ships |

| Total Base Construction Cost (1980s expansion) | $400–$500 million |

| Construction Completed | 1986 |

| Antenna Facility (new) | 34-metre antenna (completed 2021) |

| Radomes (new) | Two 13-metre radomes (completed 2021) |

Sources: Naval Technology – NSF Diego Garcia; Wikipedia – Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia; FlightGear Wiki – NSF Diego Garcia

The infrastructure numbers at Diego Garcia are genuinely staggering for an island that measures just 17 square miles. The 3,659-meter runway — one of the longest in the entire Indian Ocean region — was designed precisely to accommodate the heaviest strategic bombers in the US inventory, including the B-52 Stratofortress, B-1 Lancer, and B-2 Spirit stealth bomber. The runway’s BAK-12 arresting systems at both ends reflect the base’s readiness to recover aircraft under emergency conditions, a feature that speaks to its role in high-intensity combat operations. The deep-water port, with 20 lagoon anchorages capable of handling the largest vessels in the American or British fleet, was a major outcome of the $400–500 million expansion program authorized in the early 1980s following the Iran hostage crisis.

The 1,340,000-barrel fuel storage capacity is perhaps the single most telling statistic about Diego Garcia’s role as a forward logistics hub. In any large-scale military operation — whether in the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, or beyond — Diego Garcia functions as the “gas station and ammunition depot” of the Indian Ocean. The 20 prepositioned logistics ships of Maritime Prepositioning Ship Squadron Two (MPSRON 2) anchored in the lagoon carry tanks, armored personnel carriers, ammunition, spare parts, and even a mobile field hospital, ready to deploy to any conflict zone on short notice. This is not a garrison base — it is a strategic power projection platform, and the infrastructure data confirms it unambiguously.

Diego Garcia Base — Personnel and Staffing Statistics

| Personnel Category | Approximate Number |

|---|---|

| Total Population on Island (2026) | ~4,000 (military and civilian) |

| Military Personnel (US) | ~360 permanently stationed |

| Base Operations Support Contractors (BOSC) | ~1,800 |

| Military Sealift Command (MSC) Mariners | ~300 |

| Civilian Personnel | ~220 |

| Overseas Government Employees | ~80 |

| British Military Personnel (Naval Party 1002 / NP1002) | 40–50 |

| Pre-1966 Population (historical) | 924 (plantation contract workers) |

| Chagossians Expelled (1968–1973) | ~2,000 |

| Year First Women Stationed | 1982 |

Sources: Naval Technology – NSF Diego Garcia; Wikipedia – Diego Garcia; Wikipedia – Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia

The staffing breakdown at Diego Garcia in 2026 reveals something critical about how modern US forward bases are structured: the 1,800 BOSC contractor employees vastly outnumber the roughly 360 permanently stationed military personnel. This contractor-heavy model, managed by KBR (which runs base operations support services), reflects a broader Pentagon trend of outsourcing base logistics, maintenance, and services to civilian contractors while keeping the uniformed military footprint lean. The 300 Military Sealift Command mariners aboard the prepositioned ships in the lagoon add another layer of operational depth that standard troop counts don’t fully capture.

The 40–50 British military personnel from Naval Party 1002 (NP1002) handle the island’s civil administration and maintain the UK’s formal presence on what is technically a British Indian Ocean Territory facility. Their small number belies the legal and political importance of their presence — without them, the “joint UK-US base” designation would be little more than a formality. When operational surges occur — as satellite imagery confirmed in February 2026 with at least six military aircraft on the runway — temporary personnel numbers can rise significantly above the baseline ~4,000 figure, reflecting Diego Garcia’s design as a surge-capable platform rather than a static garrison.

Diego Garcia Base — Strategic Distance & Reach Statistics

| Target Region / Location | Distance from Diego Garcia |

|---|---|

| Strait of Hormuz (Persian Gulf entry) | ~3,800 km (2,360 miles) |

| Bab-el-Mandeb Strait (Red Sea entry) | ~3,800 km (2,360 miles) |

| Strait of Malacca (Southeast Asia) | ~3,800 km (2,360 miles) |

| Iran (Natanz nuclear site) | ~3,900 km (2,425 miles) |

| Iran (Fordow nuclear site) | ~4,000 km (2,485 miles) |

| Maldives | 726 km (451 miles) |

| Somalia coast | 2,984 km (1,854 miles) |

| Tanzania coast | 3,535 km (2,197 miles) |

| Mauritius (nearest major land) | ~1,250 miles (2,012 km) |

| India (southern tip) | ~1,796 km (1,116 miles) |

| Australia (western coast) | ~2,800 km |

| B-2 Spirit strike range (unrefueled) | 11,100 km — can strike from Diego Garcia and return |

| B-52 strike range | 14,000+ km with aerial refueling |

Sources: Wikipedia – Diego Garcia; Gulf News – US-Iran Tensions (February 2026); Chatham House – Trump, Diego Garcia and the ‘Donroe Doctrine’

The distance statistics above explain, better than any written description could, exactly why Diego Garcia matters so much in 2026. The base sits at roughly equidistant points from the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, the Strait of Hormuz, and the Strait of Malacca — the three most strategically critical maritime chokepoints in the Indo-Pacific region. This geometry is not accidental. As Chatham House noted in January 2026, Diego Garcia is equidistant from both ends of the critical sea lanes, allowing the US to project power across the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia from a single location that is free from the political and diplomatic constraints that affect US bases in countries like Qatar, Saudi Arabia, or the UAE.

Perhaps most operationally significant is the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber’s unrefueled combat range of approximately 11,100 km, which means a B-2 launched from Diego Garcia can reach virtually any target in Iran — including the hardened underground nuclear facilities at Fordow and Natanz — and return without requiring aerial refueling. This single fact explains why military analysts consistently describe Diego Garcia as the most likely launch point for any future US military strikes on Iran. The deployment of KC-135R aerial refueling tankers reported at the base in early 2026 extends this reach even further, enabling B-52s to conduct missions across the entire Indo-Pacific theater with near-unlimited range.

Diego Garcia Base — UK-Mauritius Treaty & Lease Cost Statistics

| Treaty Data Point | Figure / Detail |

|---|---|

| Treaty Signed | May 22, 2025 |

| Parties | United Kingdom & Mauritius |

| Negotiation Rounds | 13 rounds over 2+ years |

| Lease Period (Initial) | 99 years |

| Possible Extension | Additional 40 years (by mutual agreement) |

| Annual Cost to UK (first 3 years) | £165 million per year |

| Annual Cost to UK (years 4–13) | £120 million per year |

| Average Annual Cost (99-year period, 2025/26 prices) | £101 million (~$136 million USD) |

| Net Present Value of Deal (UK govt estimate) | £3.4 billion (~$4.6 billion USD) |

| Nominal Cost (Conservative Party estimate, cash terms) | ~£34.7–35 billion |

| Chagossian Trust Fund | £40 million (one-time, year 2) |

| Annual Development Grant to Mauritius | £45 million per year for 25 years (from year 4) |

| Buffer Zone (UK/US control) | 24 nautical miles around Diego Garcia |

| Immediate Leaseback Area | Diego Garcia + 12 nautical miles surrounding the island |

| Trump Reaction (January 2026) | Called deal “an act of GREAT STUPIDITY” on Truth Social |

| Expected Treaty Ratification | Sometime in 2026 (pending UK and Mauritius parliamentary processes) |

Sources: Library of Congress – In Custodia Legis (July 2025); House of Commons Library Research Briefing CBP-10273 (February 2026); Full Fact – Chagos Deal True Cost; NPR – January 2026

The numbers behind the UK-Mauritius Chagos deal are both historic and hotly contested in 2026. The UK government’s figure of £3.4 billion as the “net present value” of the agreement uses a discounting methodology that the Conservative opposition has challenged, preferring the nominal cash-terms figure of approximately £34.7–35 billion — a more than ten-fold difference depending on which accounting methodology you apply. What is not in dispute is the annual headline payment: in the first three years of the deal, the UK will pay £165 million per year to Mauritius for the right to lease Diego Garcia. This drops to £120 million per year for years four through thirteen, before being indexed to inflation for the remainder of the 99-year period.

The £40 million Chagossian Trust Fund and the £45 million per year development grant to Mauritius for 25 years are the deal’s political sweeteners — the elements designed to address both the historical injustice of the Chagossian expulsion and Mauritius’s economic development goals. Yet the agreement has drawn sharp criticism from UN human rights experts, who published a joint statement in June 2025 arguing that it “fails to guarantee” the rights of the Chagossian people, including their right to return. President Trump’s January 2026 social media attack on the deal — calling it an “act of GREAT STUPIDITY” — injected fresh geopolitical uncertainty into the ratification process, though analysts broadly agree the 99-year operational lease ensures continuity of US military operations at Diego Garcia regardless of the sovereignty transfer.

Diego Garcia Base — Operational & Combat History Statistics

| Operation / Conflict | Year(s) | Assets Deployed from Diego Garcia |

|---|---|---|

| Operation Desert Storm (Gulf War) | 1990–1991 | B-52 bombers; MPSRON 2 logistics to Saudi Arabia |

| Operation Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan) | 2001–2006 | B-1, B-2, B-52 bombers (ops began Oct 7, 2001) |

| Operation Iraqi Freedom (Iraq War) | 2003 | B-52 bombers; MPSRON 2 prepositioned ships |

| Soleimani Assassination Response Deterrence | January 2020 | At least 6 x B-52 Stratofortress deployed |

| Houthi Strikes in Yemen | 2024–2025 | B-2 Spirit, B-52 bombers |

| Israel-Iran War Deterrence (12-day conflict) | June 2025 | At least 6 bombers + 2 aerial refueling aircraft |

| Current Activity (Feb 1, 2026) | February 2026 | At least 6 aircraft confirmed on runway (satellite imagery) |

| B-1 bomber loss | December 12, 2001 | 1 B-1 lost to mechanical failure on takeoff; crew rescued by USS Russell |

| Indo-Pacific deterrence mission | 2024 | 2 x B-52 Stratofortress deployed |

| Bomber Ops Ceased (normal rotation) | August 15, 2006 | Operations temporarily wound down post-Iraq/Afghanistan peak |

Sources: Wikipedia – Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia; Misbar/Al Araby TV analysis (February 7, 2026); Gulf News (February 2, 2026)

The operational history of Diego Garcia reads like a timeline of every major US military engagement since the early 1990s. From supplying Operation Desert Storm with the logistics backbone of the Gulf War to launching B-2 stealth bomber missions against Taliban and Al-Qaeda targets in Afghanistan starting October 7, 2001, the base has been at the sharp end of US combat power for over three decades. The January 2020 deployment of at least six B-52 Stratofortress bombers following the US killing of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani demonstrated the base’s role as a rapid deterrence platform — the aircraft were there within days to signal American resolve to Tehran. The base served a similar function ahead of the June 2025 Israel-Iran conflict, when satellite imagery recorded at least six bombers and two aerial refueling aircraft positioned at the facility.

The February 1, 2026, satellite imagery — captured by both Sentinel Hub and the Chinese satellite MizarVision — showing at least six aircraft on the Diego Garcia runway is the most current operational data point available as of today. Analysts at Misbar, reporting on February 7, 2026, interpreted this buildup in the context of ongoing US-Iran tensions that have simmered through late 2025 and into 2026. The arrival of a Boeing C-17A Globemaster III operated by the British Army on January 26, 2026, and the entry of the US-flagged cargo vessel SLNC STAR into the base’s port on February 2, 2026, further confirm active supply chain and logistics activity at the base. Diego Garcia is not in standby mode — it is operating at a sustained operational tempo.

Diego Garcia Base — Surveillance, Intelligence & Space Capabilities Statistics

| System / Capability | Detail |

|---|---|

| GPS Ground Control Station | One of 5 global GPS control bases (US military-operated) |

| GPS Satellites Synchronized | 24 orbiting GPS satellites — clocks updated via Diego Garcia |

| GEODSS Facility | Ground-based Electro-Optical Deep Space Surveillance — tracks deep-space satellites |

| GEODSS Operator | Serco Inc., Herndon, Virginia |

| GEODSS Unit | Det 2, Space Operations Command |

| Satellite Control Network | Det 1, 21st Space Operations Squadron (Remote Tracking Station, Space Ops Command) |

| HFGCS Transceiver | High Frequency Global Communications System — remotely operated from Joint Base Andrews |

| Naval Computer & Telecom Station | NCTS Far East Detachment Diego Garcia |

| Air Traffic Control | Manages AMC (Air Mobility Command) traffic across Indian Ocean region |

| Reconnaissance Aircraft Deployed | Global Hawk drones, P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft |

| Electronic/Cyber Capabilities | Advanced electronic equipment for surveillance and cyber operations (per foreign reports) |

Sources: Wikipedia – Diego Garcia (Military Fandom); Naval Technology – NSF Diego Garcia; Gulf News (February 2026)

The intelligence and space capabilities housed at Diego Garcia are among the least-discussed but arguably most consequential aspects of the base’s mission in 2026. The fact that Diego Garcia serves as one of only five global GPS control stations means this tiny island atoll plays a role in the daily navigation of billions of people worldwide — from commercial aviation to smartphone mapping. The 24 orbiting GPS satellites that power the Global Positioning System have their atomic clocks synchronized and updated, in part, via the ground station on Diego Garcia. Disabling or compromising this base would ripple across global navigation infrastructure in ways that go far beyond its military mission.

The GEODSS (Ground-based Electro-Optical Deep Space Surveillance) system, operated by Serco Inc. under contract, tracks deep-space satellites and is a critical node in the US military’s space domain awareness network. Combined with the 21st Space Operations Squadron detachment, Diego Garcia is an active participant in the increasingly contested domain of space operations. The deployment of P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft — reported at the base in early 2026 — adds a crucial undersea domain awareness capability, enabling the base to track submarine activity across the Indian Ocean in real time. This multi-domain intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capability is what separates NSF Diego Garcia from a simple airstrip in the ocean.

Diego Garcia Base — Geopolitical Risk & Controversy Statistics

| Issue / Event | Year / Detail |

|---|---|

| ICJ Advisory Opinion (Mauritius sovereignty) | 2019 — UK “under obligation” to end BIOT administration |

| UN General Assembly Vote (against UK occupation) | 2019 — 116 to 6 in favor of condemning UK presence |

| Chagossian Compensation (UK payment) | 1982 — $6,000 per person (widely criticized as inadequate) |

| UK-Mauritius negotiations began | 2022 |

| Treaty Signed | May 22, 2025 |

| UN Experts Criticism of Deal | June 2025 — 4 UN officials called deal inadequate for Chagossian rights |

| UN CERD Concern | 2025 — Committee on Elimination of Racial Discrimination expressed “deep concern” |

| High Court Challenge by Chagossians | May 22, 2025 — filed day of treaty signing; temporary injunction issued |

| Trump Criticism of Deal | January 20, 2026 — called it “act of GREAT STUPIDITY” on Truth Social |

| Iran Threat to Diego Garcia | Multiple years — Iran has publicly threatened “pre-emptive strikes” on the base |

| Estimated cost (Conservative MP claim, nominal) | ~£35 billion over 99 years |

| Mauritius-China trade/economic ties | Ongoing — cited as US/UK security concern regarding base proximity |

| UK Lease Expiry (without deal) | 2036 |

Sources: Wikipedia – Chagos Archipelago Sovereignty Dispute; Library of Congress – In Custodia Legis (July 2025); House of Commons Library CBP-10273; NPR (January 2026); Misbar (February 2026)

The geopolitical story around Diego Garcia in 2026 is as complex as any in modern international relations. The 116-to-6 United Nations General Assembly vote in 2019 condemning the UK’s presence in the Chagos Archipelago reflected the near-universal international legal consensus that British administration of the islands was illegitimate — yet the UK resisted for years before finally signing the May 2025 sovereignty transfer agreement. The International Court of Justice’s 2019 advisory opinion that the UK was “under an obligation to end its administration as rapidly as possible” provided the legal pressure that ultimately forced London to the negotiating table after 13 rounds of talks over more than two years.

The $6,000-per-person compensation paid to Chagossians in 1982 — often cited by human rights advocates as one of the most shameful aspects of the base’s history — remains a raw wound. The new deal’s £40 million Chagossian Trust Fund represents a significant upgrade in intent, if not yet in justice for those expelled. Meanwhile, concerns about Mauritius’s growing economic ties to China — cited repeatedly by Trump administration officials and UK Conservative MPs — underline the geopolitical stakes of the sovereignty transfer. Any scenario in which Chinese commercial or dual-use infrastructure gains a foothold on the outer islands of the Chagos Archipelago, within proximity to Diego Garcia, represents a scenario that both Washington and London are structurally committed to preventing under the terms of the 2025 treaty’s 24-nautical-mile buffer zone.

Disclaimer: This research report is compiled from publicly available sources. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is given as to the completeness or reliability of the information. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions, losses, or damages of any kind arising from the use of this report.