Cities in Greenland 2026

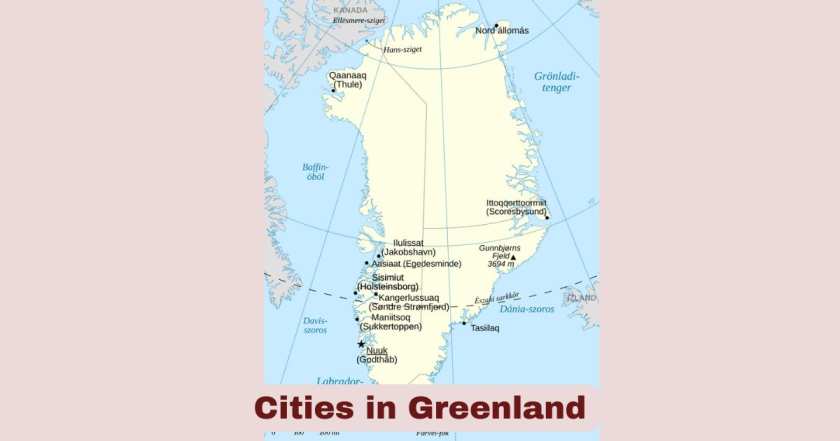

The Arctic territory of Greenland in 2026 stands as a fascinating study in extreme geography meeting human settlement. With approximately 56,831 residents as of July 2025 spread across the world’s largest island spanning 2,166,090 square kilometers, Greenland maintains the distinction of being the planet’s least densely populated territory. The cities and towns of this autonomous Danish territory cling exclusively to ice-free coastal zones, creating a unique urban pattern where modern Scandinavian infrastructure meets ancient Inuit traditions. Despite its massive landmass—larger than Mexico, Indonesia, and Libya combined—Greenland’s entire population could fit into a mid-sized sports stadium, resulting in a population density of merely 0.026 people per square kilometer.

The urban landscape of Greenland 2026 tells a compelling story of centralization and adaptation to one of Earth’s harshest environments. With 90.73 percent of the population living in urban settlements as of 2025, Greenland exhibits an urbanization rate that rivals many developed nations, though for vastly different reasons. The capital city Nuuk alone houses approximately 35 percent of the nation’s entire population, while the five largest cities collectively contain over 65 percent of all Greenlanders. This concentration reflects not luxury but necessity—the consolidation of healthcare, education, employment opportunities, and modern infrastructure in larger settlements, while smaller villages face declining populations and diminishing services. The absence of roads connecting towns means travel between settlements relies entirely on aircraft and boats, reinforcing the isolation that defines daily life across this Arctic nation.

Interesting Facts About Cities in Greenland 2026

| Fact Category | Details | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total Cities Above 1,000 Population | 12 towns (as of July 2025) | Only 12 out of 71+ settlements qualify as significant towns |

| Urbanization Rate | 90.73% living in urban areas | One of the highest urbanization rates globally |

| Largest City Dominance | Nuuk contains 35-36% of total population | Extreme centralization even by global standards |

| Top 5 Cities Population Share | Over 65% of entire population | More than half the nation lives in just 5 cities |

| Indigenous Population Percentage | 90% Inuit in Nuuk | Highest aboriginal urban percentage globally |

| Road Infrastructure | Less than 100 miles of paved roads nationwide | No roads connect any towns to each other |

| Inter-City Travel | 100% by air or sea transport | Complete reliance on aircraft and boats between settlements |

| Population Density | 0.026 people per square kilometer | Lowest population density of any country on Earth |

| Foreign-Born Residents in Capital | 19% of Nuuk’s population (2015 data) | Significantly higher diversity than smaller towns |

| Settlements Below 100 People | 30 settlements (July 2025) | Many remote villages maintaining traditional lifestyles |

| Temperature Range in Capital | From -8°C winter to 7°C summer | Arctic climate shapes all urban development |

| Number of Total Settlements | 71+ localities along coastlines | All located on ice-free coastal strips |

Data sources: Statistics Greenland 2025, Wikipedia Demographics January 2026, City Population Database 2025, UN Population Division 2025, World Bank Development Indicators 2025

The fascinating statistics about cities in Greenland 2026 reveal an urban system unlike anywhere else on the planet. The presence of only 12 towns exceeding 1,000 residents demonstrates how challenging Arctic conditions make large-scale urbanization, with the remaining settlements ranging from mid-sized villages of 200-1,000 people down to tiny hamlets of fewer than 100 inhabitants. The extraordinary urbanization rate of 90.73 percent might seem contradictory for such a sparsely populated territory, but it reflects a decades-long migration pattern from remote settlements to larger towns where employment, healthcare, and education facilities are concentrated. This urban drift has accelerated particularly toward Nuuk, which now contains more residents than the next three largest cities combined—a level of capital dominance that creates both opportunities through economies of scale and challenges through regional inequality.

The infrastructure statistics paint a picture of extreme isolation that defines urban life across Greenland. With less than 100 miles of paved roads in the entire country and zero road connections between towns, every intercity journey requires either flight or boat passage, making logistics exponentially more complex and expensive than in road-connected nations. This transportation reality fundamentally shapes urban planning, as all construction materials, food supplies, and consumer goods must arrive by sea container during the ice-free months of approximately May through November, or by expensive air freight during winter. The 19 percent foreign-born population in Nuuk, predominantly Danes attracted by salaries 50-100 percent higher than comparable Danish positions, contributes vital specialized skills but also highlights the territory’s dependence on imported expertise. Meanwhile, the 30 settlements below 100 people maintain traditional Inuit lifestyles centered on hunting, fishing, and subsistence activities, preserving cultural practices that stretch back thousands of years but facing uncertain futures as younger generations increasingly migrate to larger towns seeking modern opportunities.

Population Distribution Across Cities in Greenland 2026

| City Rank | City Name | Municipality | Population (January 2025) | Percentage of Total | Regional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nuuk | Sermersooq | 19,903 | 35.2% | National capital, government center |

| 2 | Sisimiut | Qeqqata | 5,485 | 9.7% | Second-largest city, industrial hub |

| 3 | Ilulissat | Avannaata | 5,087 | 9.0% | Tourism center, UNESCO site |

| 4 | Qaqortoq | Kujalleq | 3,069 | 5.4% | Southern regional capital |

| 5 | Aasiaat | Qeqertalik | 2,992 | 5.3% | Fishing industry center |

| 6 | Maniitsoq | Qeqqata | 2,519 | 4.5% | Historical textile production |

| 7 | Tasiilaq | Sermersooq | 1,758 | 3.1% | Eastern Greenland hub |

| 8 | Uummannaq | Avannaata | 1,401 | 2.5% | Traditional whaling community |

| 9 | Narsaq | Kujalleq | 1,257 | 2.2% | Agricultural region center |

| 10 | Paamiut | Sermersooq | 1,169 | 2.1% | Declining former trade hub |

Data source: City Population Database – Greenland Statistics January 2025, Statistics Greenland Official Estimates 2025

The population distribution across cities in Greenland 2026 reveals a dramatically top-heavy urban hierarchy where the capital’s dominance is overwhelming. Nuuk’s 19,903 residents represent more than one-third of the entire national population, a concentration level that exceeds most national capitals globally when measured as a percentage of total population. The gap between Nuuk and the second-largest city Sisimiut is stark—Nuuk contains nearly four times as many residents, creating a primate city pattern where the capital functions as the sole true metropolitan center with comprehensive urban amenities including universities, specialized hospitals, diverse employment sectors, and international connections. This concentration has accelerated over the past 50 years, driven by government employment, better educational opportunities, and the concentration of high-paying professional positions in the capital.

The middle tier of Greenlandic cities, from Ilulissat through Maniitsoq, represents regional centers serving specific geographic areas or economic functions. Ilulissat, with its 5,087 inhabitants, benefits enormously from tourism drawn to the spectacular Ilulissat Icefjord UNESCO World Heritage Site where massive icebergs calve from the Sermeq Kujalleq glacier. This tourism revenue supports infrastructure and services beyond what population size alone would justify. Qaqortoq serves as the capital of southern Greenland’s Kujalleq municipality, while Aasiaat remains a vital fishing industry center. The smaller cities from Tasiilaq downward face particular challenges—populations barely sufficient to support specialized services, aging demographics as youth migrate to larger centers, and uncertain economic futures as traditional industries decline. The combined population of the top 10 cities totals approximately 44,640 people, representing roughly 79 percent of Greenland’s entire population and illustrating the extreme concentration that characterizes this Arctic urban system.

Municipality-Level Population Statistics in Greenland 2026

| Municipality Name | Abbreviation | Capital City | Area (km²) | Population (January 2025) | Major Cities Included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sermersooq | SMS | Nuuk | 575,300 | 24,229 | Nuuk, Tasiilaq, Paamiut, Ittoqqortoormiit |

| Avannaata | AVA | Ilulissat | 522,700 | 10,989 | Ilulissat, Uummannaq, Qaanaaq, Upernavik |

| Qeqqata | QQT | Sisimiut | 97,000 | 9,179 | Sisimiut, Maniitsoq, Kangerlussuaq |

| Qeqertalik | QTL | Aasiaat | 62,400 | 5,969 | Aasiaat, Qasigiannguit, Kangaatsiaq |

| Kujalleq | KJL | Qaqortoq | 51,000 | 6,110 | Qaqortoq, Narsaq, Nanortalik |

Data source: City Population Database – Greenland Municipalities January 2025, Kalaallit Nunaanni Naatsorsueqqissaartarfik Official Statistics

The five municipalities that comprise Greenland 2026 demonstrate the administrative challenge of governing vast Arctic territories with tiny, scattered populations. Sermersooq Municipality, despite containing the capital Nuuk, spans an enormous 575,300 square kilometers—an area larger than France—yet houses only 24,229 people. This municipality uniquely extends across both west and east coasts, encompassing the isolated eastern settlement of Ittoqqortoormiit with just 324 residents, one of the world’s most remote inhabited communities accessible only by helicopter or boat during limited ice-free periods. The municipality’s population concentration in Nuuk creates significant governance challenges, as the capital’s needs and priorities often differ dramatically from those of small settlements hundreds of kilometers away.

Avannaata Municipality in northwestern Greenland represents the opposite challenge—enormous geographic area (522,700 square kilometers) with population dispersed among multiple towns rather than concentrated in one dominant center. While Ilulissat serves as the municipal capital with 5,087 residents, other significant towns including Uummannaq (1,401), Qaanaaq (598), and Upernavik (1,067) maintain distinct regional identities and economic bases, from whaling traditions to research station support near the Thule Air Base. The southern municipalities of Kujalleq and Qeqertalik have experienced the most significant population decline over recent decades, with Kujalleq dropping from over 8,000 residents in 2000 to just 6,110 in 2025—a 24 percent decline reflecting youth emigration, economic stagnation, and the collapse of traditional industries. This municipal-level data reveals how cities in Greenland 2026 operate within a governance structure struggling to deliver services across Arctic distances to populations barely sufficient to support modern urban infrastructure.

Economic Structure of Cities in Greenland 2026

| Economic Sector | Employment Share | Key Cities Involved | Annual Output/Value | Growth Trend 2020-2025 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fishing Industry | 12.5% of workforce | Sisimiut, Aasiaat, Nuuk, Qaqortoq | 90% of export income | Stable with quota variations |

| Public Sector | 40.3% of workforce | Nuuk, Ilulissat, Qaqortoq | 10,307 jobs nationally | Growing slowly |

| Tourism Services | 8-10% (seasonal) | Ilulissat, Nuuk, Qaqortoq | 450 million DKK (2019 peak) | Recovering post-COVID |

| Wholesale/Retail Trade | 30% of company turnover | All major cities | ~33% business revenue | Moderate growth |

| Mining Operations | <2% direct employment | Limited (2 active mines 2025) | Exploratory stage mostly | Uncertain future |

| Transportation | 5-7% of workforce | Nuuk, Kangerlussuaq, Ilulissat | Essential connectivity | Infrastructure expansion |

Data sources: Economy of Greenland Wikipedia 2026, Statistics Greenland Employment Data 2024, Greenland in Figures 2025, Visit Greenland 2025

The economic foundation of cities in Greenland 2026 rests on a surprisingly narrow base dominated by fishing, public employment, and Danish subsidies. The fishing industry, centered on cold-water shrimp and Greenland halibut, employs one in eight Greenlanders (12.5 percent of the workforce) and generates nearly 90 percent of export income, making it the indispensable economic pillar upon which most coastal cities depend. Royal Greenland, the world’s largest retailer of cold-water shrimp, operates 38 large-scale factories plus numerous smaller facilities in cities and towns nationwide, with major processing plants in Nuuk, Sisimiut, Aasiaat, Qaqortoq, and other coastal settlements. The factory in Nuuk alone produces nearly 2,000 tonnes of fish, cod, and halibut annually, though managers characterize this as a medium-sized operation compared to others. This concentration creates vulnerability—quotas, fish stock fluctuations, and international market prices directly impact municipal budgets and employment levels across fishing-dependent cities.

The public sector plays an outsized role that would be unsustainable without external support, employing 10,307 Greenlanders out of approximately 25,620 in the total workforce as of recent data—roughly 40 percent of all employment. This massive government presence concentrates overwhelmingly in Nuuk, where ministries, agencies, Parliament, courts, and national institutions provide stable, high-paying positions that drive the capital’s prosperity and attract migrants from smaller settlements. Government salaries in Nuuk average more than twice those in other parts of Greenland, creating a powerful economic gradient that accelerates urbanization toward the capital. The tourism sector, generating approximately 450 million DKK (roughly 67 million USD) in 2019 before COVID-19 disruptions, has become increasingly important for Ilulissat where visitors to the UNESCO-listed Icefjord support hotels, restaurants, tour operators, and related services. Tourism growth rates of 20 percent annually in 2015-2016 and subsequent recovery post-pandemic position this sector as a potential diversification path, though seasonal employment patterns and concentration in just a few cities limit its transformative potential. The critically important fact remains that Danish subsidies averaging 5.4 billion DKK (approximately 724 million EUR) annually from 2019-2023 constitute over 20 percent of Greenland’s GDP, subsidizing government operations, infrastructure, and services that the domestic economy alone could never support across such vast distances with such small populations.

Infrastructure and Connectivity in Cities in Greenland 2026

| Infrastructure Type | National Total | Capital City Capacity | Regional Coverage | Development Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paved Roads | <100 miles nationwide | Limited within Nuuk city limits | No inter-city roads exist | Minimal expansion planned |

| Airports | 13 airports (with scheduled service) | Nuuk Airport (GOH) | All major towns accessible | Nuuk/Ilulissat expansions 2024-2025 |

| Seaports | 71+ harbors (various sizes) | Nuuk container port (world-class) | Every settlement has dock | Ice-limited November-May |

| Healthcare Facilities | 1 national hospital (Nuuk) | Dronning Ingrids Hospital | Regional health centers | Specialized care requires Denmark |

| Higher Education | 1 university (Nuuk) | University of Greenland | 12 bachelor, 4 master programs | Limited program diversity |

| Internet/Telecom | Fiber/satellite coverage | Full high-speed in Nuuk | Variable in smaller towns | Ongoing improvements |

| Housing Units | ~25,000 units nationally | ~9,000 units in Nuuk | Shortages in growing cities | Construction ongoing |

| Power Generation | 70% renewable (hydropower) | Multiple hydro plants near Nuuk | Diesel generators in remote areas | Expansion projects active |

Data sources: Nuuk Wikipedia Infrastructure 2026, Economy of Greenland Wikipedia 2026, Greenland in Figures 2025, Statistics Greenland 2024

The infrastructure reality of cities in Greenland 2026 creates unique constraints that shape every aspect of urban life. The absence of roads connecting towns—a consequence of permafrost, ice sheet proximity, and the prohibitive expense of Arctic road construction across such vast distances—means every intercity journey requires aircraft or boat. Air Greenland, the government-owned national carrier, operates the lifeline network connecting settlements through a hub-and-spoke system centered on Kangerlussuaq international airport and regional airports in Nuuk, Ilulissat, Sisimiut, and other major towns. The recent airport expansion projects, with Nuuk’s new runway completed in late 2024 and Ilulissat’s expansion finished in 2025, now accommodate large passenger aircraft and can manage 800 and 600 passengers per hour respectively, dramatically improving international connectivity and tourism potential after decades of relying on smaller aircraft requiring layovers in Iceland or Kangerlussuaq.

Maritime infrastructure remains absolutely critical, as the ice-free navigation season from approximately May through November represents the primary window for bulk cargo delivery. The Sikuki Nuuk Harbour A/S container port serves as Greenland’s maritime gateway, with facilities for container traffic, trawler support, cruise ship docking, and capacity for large-volume transit cargo that supplies the entire western coast. During winter months, supplies arrive by expensive air freight, adding dramatically to the cost of living in all Greenlandic cities. The single national hospital (Dronning Ingrids Hospital) in Nuuk provides the highest level of healthcare available within Greenland, with regional health centers in other major towns, but highly specialized treatments—certain cancer therapies, complex cardiac procedures, advanced neurosurgery—require patient transfer to hospitals in Denmark, typically Copenhagen, with costs covered by Greenland’s healthcare system. This arrangement reflects the economic impracticality of maintaining full tertiary care capabilities for a population of just 56,000 spread across thousands of kilometers. The University of Greenland in Nuuk offers only 12 bachelor programs and 4 master programs, forcing students seeking most professional degrees (law, medicine, engineering) to study abroad, predominantly in Denmark, contributing to the brain drain as graduates often fail to return.

Housing and Living Conditions in Cities in Greenland 2026

| Housing Metric | Capital City (Nuuk) | Second-Tier Cities | Small Towns (<2,000) | National Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Rent (1-bedroom) | 6,000-8,000 DKK/month | 4,000-6,000 DKK/month | 3,000-4,500 DKK/month | ~5,000 DKK/month |

| Home Ownership Rate | ~55% | ~60% | ~65% | ~60% |

| Average Household Size | 2.8 persons | 3.1 persons | 3.4 persons | 3.0 persons |

| Housing Units Built 2020-2025 | ~1,000 units | ~300 units combined | <100 units total | ~1,400 units |

| Waiting List for Social Housing | 2-3 years typical | 1-2 years | 6-12 months | Varies significantly |

| Construction Costs per m² | ~25,000 DKK | ~28,000 DKK | ~30,000+ DKK | Extremely high everywhere |

| Heating Costs (annual) | 15,000-25,000 DKK | 18,000-28,000 DKK | 20,000-35,000 DKK | ~22,000 DKK |

| Modern Amenities (%) | 95%+ | 85-90% | 70-80% | ~85% |

Data sources: Visit Greenland Housing Data 2025, Statistics Greenland Social Services 2024, Nuuk Wikipedia Housing Section 2026

Housing represents one of the most acute challenges facing cities in Greenland 2026, with chronic shortages in growing cities like Nuuk and aging, inadequate housing stock in declining settlements. The capital’s rental market, with one-bedroom apartments commanding 6,000-8,000 DKK monthly (approximately 800-1,070 EUR), reflects both strong demand from the concentrated population and the extraordinarily high construction costs inherent in Arctic building. All construction materials except local stone must be imported by sea, while the short building season limited by Arctic weather, specialized cold-climate construction requirements including permafrost considerations, expensive heating systems, and premium wages required to attract construction workers drive costs to levels that would be prohibitive in southern climates. These factors result in construction costs exceeding 25,000 DKK per square meter in Nuuk and even higher in more remote locations, making new housing development economically challenging despite obvious need.

The social consequences of this housing reality ripple through Greenlandic urban society. Waiting lists for social housing in Nuuk extend 2-3 years, forcing young families and lower-income residents into temporary solutions or shared accommodations that strain relationships and limit life opportunities. The higher home ownership rates in smaller towns (~65 percent) versus the capital (~55 percent) reflect both lower prices in declining communities and a demographic sorting where property owners less able or willing to abandon homes remain in shrinking settlements while renters more easily migrate to Nuuk for opportunities. Modern amenities including indoor plumbing, consistent electricity, high-speed internet, and central heating have reached near-universal coverage in major cities (95%+ in Nuuk) but remain less consistent in the smallest settlements where infrastructure maintenance challenges and high per-capita costs create gaps. Heating costs, consuming 15,000-35,000 DKK annually depending on location and building efficiency, constitute a major household expense through the long Arctic winters where January temperatures average -8°C in Nuuk and far colder in northern settlements, with modern insulation and heating systems representing essential survival infrastructure rather than luxury additions.

Demographic Characteristics of Cities in Greenland 2026

| Demographic Indicator | National Figure | Capital City | Regional Variation | Trend Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 56,831 (July 2025) | 19,903 in Nuuk | Heavily concentrated | Stable/slight decline |

| Median Age | 35.1 years | ~33 years (Nuuk) | Higher in declining towns | Aging population |

| Birth Rate | 13.23 per 1,000 | Slightly higher in cities | Lower in settlements | Declining significantly |

| Fertility Rate | 1.8 children per woman | Below replacement | Rural rates also declining | Steady decrease |

| Life Expectancy (Men) | 69.3 years | Slightly higher in Nuuk | Lower in remote areas | Slowly increasing |

| Life Expectancy (Women) | 73.9 years | ~75 years in capital | Geographic variation | Gradually improving |

| Inuit Population | 88% nationally | ~90% in Nuuk | Near 100% in villages | Stable majority |

| Foreign-Born Residents | 6,804 (12%) nationally | 19% of Nuuk population | <5% in small towns | Concentrated in capital |

| Gender Ratio | 111 males per 100 females | More balanced in Nuuk | Male surplus in work camps | Workforce-driven imbalance |

| Working-Age Population (18-64) | 65.5% of total | ~68% in Nuuk | Lower in aging towns | Declining share |

Data sources: Demographics of Greenland Wikipedia 2026, Statistics Greenland Vital Statistics 2024-2025, Worldometer Population Data 2025-2026

The demographic profile of cities in Greenland 2026 reveals a society experiencing profound transformation from traditional Arctic subsistence patterns toward modern urbanized life, though not without significant stresses. The median age of 35.1 years masks considerable variation between Nuuk, where younger working-age adults concentrate in pursuit of employment and education, and smaller declining settlements where aging populations remain after younger generations depart. The capital’s slightly younger demographic (~33 years median) reflects ongoing migration streams that systematically select younger, more educated, and more ambitious individuals, leaving older, less mobile populations in towns with declining services and economic opportunities. This age-selective migration accelerates the challenges facing regional centers, as tax bases shrink, schools close due to insufficient enrollment, and healthcare facilities struggle to justify specialized staff for aging populations.

The fertility rate collapse to just 1.8 children per woman in 2024 represents one of the most significant demographic developments, falling from over 2 children per woman as recently as 2020 and dramatically below the replacement rate of 2.1. This decline has occurred across all settlement types, shattering earlier assumptions that rural areas would maintain higher fertility supporting traditional lifestyles. The approximately 700 births annually nationwide—barely 2 births per day—barely exceeds the 500 deaths, generating minimal natural increase of roughly 200 people insufficient to offset net emigration of 300-400 annually to Denmark or other countries. Life expectancy figures reveal persistent health disparities, with Greenlandic men living to 69.3 years—significantly below Western averages—primarily due to high mortality from accidents and suicide, particularly affecting younger males in remote settlements facing limited opportunities and social stresses. The gender imbalance of 111 males per 100 females nationally reflects the imported workforce dominated by men (2/3 male, 1/3 female among foreign-born workers), particularly in industries like fishing and construction where physical demands and harsh conditions have historically attracted male workers, though this pattern is gradually shifting as service sector employment grows in importance across cities in Greenland 2026.

Education and Healthcare Access in Cities in Greenland 2026

| Service Type | National Availability | Capital Access | Regional Access | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Schools | ~60 schools nationally | 8+ schools in Nuuk | Every town has primary school | Teacher recruitment |

| Secondary Schools | ~15 institutions | 4 institutions in Nuuk | Major towns only | Limited programs |

| Vocational Training | Multiple centers | Main center in Nuuk | Regional centers exist | Industry-specific |

| University Education | 1 university (Nuuk only) | Full bachelor/master access | None outside capital | Must study abroad |

| Hospitals | 1 national hospital (Nuuk) | Comprehensive services | Regional health centers | Specialization limited |

| Doctors per 1,000 | ~1.8 per 1,000 | ~3.0 per 1,000 in Nuuk | <1.0 in small towns | Severe shortage |

| Dental Services | Public clinics in towns | Multiple clinics in Nuuk | Limited in villages | Free for residents |

| Emergency Medical Transport | Helicopter/plane service | Ambulance within Nuuk | Air evacuation required | Weather-dependent |

| Mental Health Services | Critically understaffed | Better access in Nuuk | Minimal in small towns | Major gap |

| Medical Evacuation to Denmark | ~200 cases annually | Coordinated from Nuuk | Cancer/cardiac/neuro cases | Expensive necessity |

Data sources: Greenland in Figures 2025, Statistics Greenland Social Services Data 2024, Nuuk Wikipedia Education/Healthcare Sections 2026

Education infrastructure across cities in Greenland 2026 reveals the severe constraints of serving scattered populations across vast distances. While every town maintains at least a primary school ensuring children can access basic education near home, the quality and comprehensiveness of educational offerings decline sharply with settlement size. Small village schools often operate with just one or two teachers serving all grade levels, while Nuuk’s schools can offer specialized instruction, better facilities, and comprehensive programs. The transition to secondary education forces many students from smaller settlements to board in larger towns, creating social disruption as teenagers leave families, though this long-standing pattern is accepted as necessary reality. The critical bottleneck emerges at university level—the University of Greenland offers only 12 bachelor programs and 4 master programs, forcing students seeking professional degrees in law, medicine, engineering, business, and most academic disciplines to study abroad, predominantly in Denmark where language and cultural ties ease transition.

This educational migration creates a devastating brain drain, as graduates earning degrees in Copenhagen, Aarhus, or other Danish cities frequently fail to return to Greenland’s limited job market, harsh climate, and significantly lower salaries in private sector positions. The result perpetuates Greenland’s dependence on imported expertise, particularly visible in healthcare where the doctor shortage affects all cities except the capital. Nuuk’s Dronning Ingrids Hospital, the national facility, employs specialists in many fields and can perform most routine procedures, but highly specialized treatments—certain cancer therapies requiring radiation equipment too expensive to maintain for such small patient numbers, complex cardiac procedures, advanced neurosurgery—necessitate patient transfer to hospitals in Denmark, typically Copenhagen’s Rigshospitalet. Approximately 200 patients annually make these medical evacuation journeys, with Greenland’s healthcare system covering costs but patients facing the stress of treatment far from home and family. Mental health services remain critically understaffed across all Greenlandic cities, with suicide rates, substance abuse, and depression—particularly affecting men in remote settlements—receiving insufficient therapeutic response due to the shortage of psychologists, psychiatrists, and counselors willing to practice in isolated Arctic communities, contributing to the tragedy of lives cut short and communities traumatized by repeated losses.

Climate Impact on Cities in Greenland 2026

| Climate Factor | Capital (Nuuk) | Northern Cities | Southern Towns | Urban Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average January Temperature | -8°C | -20°C to -25°C | -6°C to -8°C | Heating costs vary dramatically |

| Average July Temperature | 7°C | 5°C to 8°C | 8°C to 10°C | Short construction season |

| Annual Precipitation | 750 mm | 200-400 mm | 800-1,200 mm | Infrastructure design impact |

| Snow Cover Duration | 6-7 months | 8-9 months | 5-6 months | Transportation disruption |

| Ice-Free Port Months | May-November | July-September | April-December | Supply chain critical |

| Daylight Hours (December) | 4.4 hours | 0 hours (polar night) | 5-6 hours | Psychological effects |

| Daylight Hours (June) | 21 hours | 24 hours (midnight sun) | 20 hours | Sleep disruption, tourism |

| Permafrost Presence | Discontinuous | Continuous | Sporadic/absent | Building foundation challenges |

| Ice Sheet Proximity | ~40 km from city | Variable distances | 100+ km | Glacial melt affecting ports |

| Annual Temperature Rise (2000-2025) | +1.2°C | +1.5°C | +1.0°C | Accelerating infrastructure stress |

Data sources: Climate of Greenland Data 2025, Nuuk Wikipedia Climate Section 2026, Arctic Climate Research 2024-2025

The Arctic climate fundamentally shapes every aspect of urban life across cities in Greenland 2026, imposing costs and constraints unimaginable in temperate zones. The capital Nuuk’s average January temperature of -8°C requires residential buildings to maintain heating systems capable of overcoming 45-50°C temperature differentials between interior comfort and exterior cold, while northern cities like Qaanaaq endure far harsher conditions with winter temperatures plummeting to -20°C or below and experiencing complete polar night from November through January when the sun never rises above the horizon. These extreme conditions drive heating costs that consume 15-25 percent of household budgets in the capital and even higher proportions in colder locations, making energy efficiency not merely an environmental concern but an economic survival issue for families. The psychological toll of months-long darkness, particularly affecting northern settlements, contributes to elevated rates of seasonal affective disorder, depression, and the persistently high suicide rates that plague Greenlandic society, especially impacting young men.

The short construction season imposes severe constraints on urban development across all cities in Greenland 2026. With effective building weather limited to approximately May through September—just 5 months annually—when temperatures consistently stay above freezing and daylight extends through most hours, construction projects must be meticulously planned to complete foundations, structural work, and weatherproofing within this narrow window. The ice-free navigation season similarly dictates economic rhythms, as bulk cargo deliveries during May-November (or shorter windows in northern ports) must supply cities with a full year’s building materials, consumer goods, and non-perishable supplies. This creates warehousing challenges and occasional shortages if shipping schedules face delays. Climate change impacts, while gradual, are reshaping Greenlandic cities in measurable ways—the +1.2°C temperature rise in Nuuk since 2000 extends the ice-free season slightly, potentially benefiting shipping, but simultaneously accelerates permafrost thaw beneath building foundations, threatening infrastructure integrity and requiring expensive remediation. The proximity of the Greenland Ice Sheet—just 40 kilometers from Nuuk’s city limits—serves as both spectacular backdrop and sobering reminder of the massive ice mass whose accelerating melt contributes to global sea level rise while paradoxically threatening Greenland’s coastal cities through changing ocean currents, increased iceberg hazards, and gradual port infrastructure challenges.

Transportation Networks in Cities in Greenland 2026

| Transport Mode | National Coverage | Capital Connectivity | Inter-City Service | Annual Passengers/Cargo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Greenland Routes | 13 airports with service | Hub at Nuuk Airport | All major cities connected | ~400,000 passengers annually |

| International Flights | 3 airports (Nuuk, Ilulissat, Kangerlussuaq) | Direct to Copenhagen/Reykjavik | Limited international | ~200,000 international |

| Helicopter Services | 43 heliports | Multiple pads in Nuuk | Essential for small settlements | ~50,000 passengers |

| Ferry Routes | Coastal shipping network | Nuuk Harbour operations | Arctic Umiaq Line coastal ferry | ~30,000 passengers |

| Cargo Ships | Weekly/monthly schedules | Major port at Nuuk | All coastal towns | ~250,000 tonnes annually |

| Local Bus Service | Nuuk only | 6 routes in capital | None in other cities | ~2 million rides annually |

| Taxi Services | Available in major towns | ~50 taxis in Nuuk | Limited fleet elsewhere | Essential winter transport |

| Personal Vehicles | ~7,000 registered nationally | ~3,500 in Nuuk | No inter-city driving | Local use only |

| Snowmobile Transport | Traditional in villages | Recreational in Nuuk | Essential in small settlements | Cultural/practical importance |

| Dog Sled Teams | Northern tradition | Rare in Nuuk | Active in Qaanaaq region | Heritage tourism attraction |

Data sources: Air Greenland Operations Data 2025, Nuuk Wikipedia Transport Section 2026, Statistics Greenland Transportation 2024

Transportation infrastructure represents both the lifeline and the limitation defining cities in Greenland 2026. The complete absence of roads connecting towns creates an entirely air-and-sea-dependent transportation system unique among modern territories. Air Greenland, the government-owned carrier operating a monopoly on scheduled domestic flights, maintains the crucial network linking settlements through a combination of Airbus A330 aircraft for international routes, smaller Dash-8 aircraft for major domestic routes, and helicopters serving the smallest settlements where fixed-wing landing strips are impractical. The recent completion of runway extensions at Nuuk Airport in late 2024 and Ilulissat Airport in 2025 transformed Greenland’s connectivity by enabling direct transatlantic flights, eliminating the previous requirement for international passengers to transit through Reykjavik or connect via the remote Kangerlussuaq hub built during World War II as a U.S. military base.

These improvements dramatically reduced journey times and costs—a round-trip from Copenhagen to Nuuk that previously required 12-15 hours including connections now completes in under 5 hours direct flight time, opening new tourism possibilities and easing the burden on Greenlanders traveling to Denmark for specialized medical care, education, or family visits. The Arctic Umiaq Line coastal ferry, sailing during ice-free months between Qaqortoq in the south through Nuuk to Ilulissat and Aasiaat in the north, provides more affordable transport than flying, carrying both passengers and vehicles though the 3-4 day journey tests passenger patience. Within Nuuk itself, the capital maintains Greenland’s only public bus system with 6 routes serving neighborhoods, though the modest 2 million annual rides reflect the city’s compact geography where many residents walk or use taxis. The registration of approximately 7,000 personal vehicles nationwide, with half concentrated in Nuuk, might seem surprisingly high until recognizing these vehicles travel exclusively on the limited road networks within individual towns—no Greenlandic city resident can drive to visit friends in another city, making car ownership entirely about local convenience rather than regional mobility, a transportation reality that profoundly shapes the isolation and distinctiveness that characterizes life across cities in Greenland 2026.

Economic Challenges Facing Cities in Greenland 2026

| Challenge Category | Impact Level | Most Affected Cities | Economic Cost | Mitigation Efforts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population Decline | Severe in regional centers | Paamiut, Nanortalik, Qasigiannguit | Service cuts, tax base erosion | Youth retention programs |

| High Cost of Living | Critical nationwide | All cities, especially remote | 150-200% above Denmark | Subsidy programs limited |

| Youth Emigration | Major problem | All except Nuuk | Brain drain, aging workforce | Education incentives |

| Fishing Quota Dependency | Extreme vulnerability | Aasiaat, Sisimiut, Qaqortoq | 90% of export income | Diversification initiatives |

| Housing Shortage | Acute in capital | Nuuk, Ilulissat | Construction bottlenecks | Building programs insufficient |

| Unemployment | Moderate | Varies 8-12% by city | Social costs, emigration | Limited job creation |

| Alcohol/Substance Abuse | Severe social problem | All settlements | Health, crime, family breakdown | Treatment capacity inadequate |

| Mental Health Crisis | Critical | Northern settlements especially | High suicide rates | Counseling shortage |

| Climate Infrastructure Damage | Growing concern | Coastal cities | Permafrost thaw, erosion | Adaptation expensive |

| Dependence on Danish Subsidies | Absolute necessity | Entire territory | 5.4 billion DKK annually | Independence economically impossible |

Data sources: Economy of Greenland Wikipedia 2026, Statistics Greenland Economic Indicators 2024, Greenland Social Challenges Reports 2025

The economic challenges confronting cities in Greenland 2026 create a perfect storm threatening the viability of smaller settlements while straining even the prosperous capital. Population decline in regional centers represents an accelerating crisis—Paamiut dropped from 2,237 residents in 1980 to just 1,169 in 2025, a catastrophic 48 percent decline over 45 years that gutted the tax base, forced school closures, and reduced the town from vibrant regional hub to struggling remnant. Similar trajectories affect Qasigiannguit (down from 1,771 in 1980 to 961 in 2025), Nanortalik, and numerous smaller settlements, creating a vicious cycle where service cuts drive further emigration, particularly of families with children seeking better educational opportunities. These dying towns face impossible choices—maintain expensive infrastructure for shrinking populations or accelerate decline by cutting services that make communities livable.

The cost of living burden affects all Greenlanders but impacts small-town residents especially hard. Groceries, consumer goods, and services cost 150-200 percent of equivalent Danish prices due to shipping expenses, limited competition, small-scale retail operations, and the need to import virtually everything from southern suppliers. A liter of milk might cost 12-15 DKK in Nuuk versus 7-8 DKK in Copenhagen, while prices rise further in remote settlements where helicopter delivery adds additional markups. These costs consume disproportionate shares of income for lower-wage workers in fishing or service sectors, contributing to poverty rates reaching 15-20 percent in some communities despite Denmark’s welfare support. The absolute dependence on Danish subsidies—averaging 5.4 billion DKK annually (approximately 724 million EUR)—represents over 20 percent of GDP and funds government operations, healthcare, education, infrastructure, and social services that Greenland’s economy could never support independently. This dependency, while providing higher living standards than domestic economy alone could sustain, complicates political aspirations for independence and creates vulnerability to Danish political changes or economic difficulties. The social pathologies afflicting Greenlandic cities—alcohol abuse rates among the world’s highest, suicide rates that shock international observers, domestic violence, and intergenerational trauma from colonial-era policies—impose immense human costs while consuming healthcare and social service budgets already stretched impossibly thin across such vast geography, creating challenges that no amount of subsidy can fully address without fundamental social healing that remains frustratingly elusive across cities in Greenland 2026.

Cultural Life and Urban Identity in Cities in Greenland 2026

| Cultural Aspect | National Pattern | Capital Expression | Regional Variations | Traditional vs Modern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language Usage | Kalaallisut official (Greenlandic) | Bilingual Greenlandic/Danish | Greenlandic dominant in villages | Youth increasingly Danish-proficient |

| Indigenous Heritage | 88% Inuit ethnicity | ~90% in Nuuk | Near 100% in small settlements | Traditional practices declining |

| Traditional Hunting | Cultural cornerstone | Recreational in Nuuk | Economic necessity villages | Regulated, quotas applied |

| Fishing Culture | Defines coastal identity | Industrial scale in cities | Small-boat traditional methods | Commercial transformation complete |

| Music Scene | Hip-hop/rock popular | Active venues in Nuuk | Local bands in major towns | Blend Inuit/Western influences |

| Museums/Cultural Centers | National Museum in Nuuk | 4 major museums capital | Local museums some towns | Preserving disappearing traditions |

| Traditional Clothing | National costume occasions | Ceremonial use declining | More common in villages | Expensive, special events only |

| Drum Dancing | Ancient Inuit tradition | Performance art in cities | Occasional village practice | Revival efforts ongoing |

| Christianity | 95% Lutheran Church | Strong church attendance Nuuk | Central to community life | Syncretic Inuit elements |

| Alcohol-Free Towns | 4-5 settlements | Nuuk permits alcohol | Some villages ban alcohol | Addressing abuse epidemic |

Data sources: Culture of Greenland Wikipedia 2026, Nuuk Wikipedia Culture Section 2026, Visit Greenland Cultural Information 2025

The cultural landscape of cities in Greenland 2026 navigates complex tensions between Inuit heritage spanning thousands of years and modern Scandinavian-influenced urban lifestyles. Kalaallisut, the Greenlandic language belonging to the Inuit language family, serves as the official language and primary tongue for the overwhelming majority of residents, though bilingualism with Danish remains near-universal in cities where government operations, higher education, and business often conduct affairs in Danish. The capital Nuuk exemplifies this duality—modern Nordic-style apartment buildings house residents who may speak Greenlandic at home and Danish at work, attend university lectures in Danish while Parliament conducts business in Greenlandic, and navigate daily life switching between linguistic and cultural codes that would bewilder outsiders. Younger Greenlanders, especially those educated in Danish universities or consuming primarily Danish/English media, increasingly favor Danish in casual conversation, raising concerns about Greenlandic language vitality despite its official status and school instruction.

Traditional practices persist most robustly in smaller settlements where subsistence activities retain economic importance alongside cultural meaning. Hunting seals, whales (where permitted under strict quotas), caribou, and Arctic birds continues to provide supplemental protein and maintain skills passed through generations, though modern rifles have replaced harpoons and GPS aids navigation where elders once read stars and ice patterns. In Nuuk, hunting has become largely recreational—a weekend activity for those maintaining tradition—while most residents purchase imported meat from supermarkets. The National Museum of Greenland in the capital preserves remarkable artifacts including five-hundred-year-old mummified bodies discovered in Qilakitsoq, traditional kayaks, intricate beadwork, and hunting implements, serving as reminder of the sophisticated Arctic cultures that sustained human life in this harsh environment for millennia before European contact. The contemporary music scene reflects cultural hybridization, with Greenlandic hip-hop artists rapping in Kalaallisut about urban life, identity struggles, and social issues while rock and electronic music scenes flourish in Nuuk’s venues. The persistent challenge of alcohol abuse has driven several small settlements to become completely alcohol-free through democratic vote, banning alcohol sales and importation in desperate attempts to break cycles of addiction destroying families and communities, though Nuuk and larger cities maintain legal alcohol sales while grappling with the devastating social consequences that make Greenland’s alcohol-related mortality rates among the world’s highest, a tragedy reflecting the collision between traditional social structures never designed for sedentary urban life and the stresses of rapid modernization across cities in Greenland 2026.

Future Prospects for Cities in Greenland 2026

| Development Area | Current Status | Planned Projects | Timeline | Expected Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airport Expansions | Nuuk/Ilulissat complete | Qaqortoq expansion planned | 2026-2028 | Improved southern access |

| Rare Earth Mining | Exploratory stage | Kvanefjeld uranium/REE project | Uncertain, environmental concerns | Potential economic transformation |

| Tourism Growth | Post-COVID recovery | Marketing campaigns, cruise infrastructure | 2025-2030 | 20-30% growth projected |

| Renewable Energy | 70% hydropower current | New hydro projects Nuuk region | 2025-2027 | Energy independence, lower costs |

| Fiber Optic Cable | Partial coverage | Arctic Connect submarine cable | 2026-2027 | Better internet, lower costs |

| Housing Construction | Chronic shortage | 500 units planned Nuuk | 2025-2028 | Insufficient for demand |

| University Expansion | Limited programs | New programs consideration | Long-term | Reduce study abroad necessity |

| Independence Movement | Political discussion | No concrete timeline | Decades away | Economically challenging |

| Climate Adaptation | Initial planning | Permafrost monitoring, coastal protection | Ongoing | Essential infrastructure preservation |

| Population Projection | 56,831 (2025) | Forecast ~57,000-58,000 | 2030 | Minimal growth expected |

Data sources: Greenland Development Plans 2025, Economy of Greenland Wikipedia 2026, Arctic Investment Projects 2025

The future trajectory of cities in Greenland 2026 balances ambitious development hopes against stubborn economic and demographic realities. The completed airport expansions at Nuuk and Ilulissat have already transformed international connectivity, with direct flights to North America and Europe opening tourism possibilities that were economically impractical when all visitors faced expensive connections through Iceland or Kangerlussuaq. Tourism industry projections forecasting 20-30 percent growth through 2030 assume continued recovery from COVID-19 disruptions and capitalize on growing interest in Arctic destinations, glacier tourism, northern lights viewing, and adventure travel, though this growth concentrates overwhelmingly in Ilulissat with its spectacular UNESCO icefjord and secondarily in Nuuk, providing limited benefit to struggling regional centers. The proposed Qaqortoq airport expansion, if completed by 2028, could partially address southern Greenland’s connectivity challenges and support tourism development in that region’s relatively mild climate and Norse ruins.

The most potentially transformative—and controversial—development involves rare earth element mining, particularly the massive Kvanefjeld deposit near Narsaq containing uranium, rare earth elements, and other minerals valued in the billions. This project has polarized Greenlandic society between those seeing economic salvation and path toward reduced Danish dependency versus those fearing environmental devastation, radioactive contamination, and destruction of the fishing industry upon which coastal cities depend. The 2021 parliamentary elections saw the pro-mining party lose power partly due to Kvanefjeld concerns, leaving the project in limbo and Greenland’s economic diversification dreams unrealized. Even if eventually approved, mining operations would take years to develop, employ relatively few Greenlanders due to specialized skill requirements, and risk environmental catastrophe if waste management fails in this sensitive Arctic ecosystem. The renewable energy expansion, with new hydropower projects planned near Nuuk potentially increasing electricity generation by 25-30 percent, offers more certain benefits through lower energy costs and reduced diesel dependency, though financing these expensive Arctic infrastructure projects challenges government budgets. The population projection of just 57,000-58,000 by 2030 reflects demographic reality—fertility rates below replacement, ongoing emigration of educated youth, and limited immigration—suggesting the fundamental challenge facing cities in Greenland 2026 is managing gradual decline in smaller settlements while supporting continued concentration in Nuuk, accepting that economic forces and human preferences will continue reshaping this Arctic urban system toward greater centralization regardless of policy preferences for balanced regional development.

Disclaimer: This research report is compiled from publicly available sources. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is given as to the completeness or reliability of the information. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions, losses, or damages of any kind arising from the use of this report.