Greenland National Park 2026

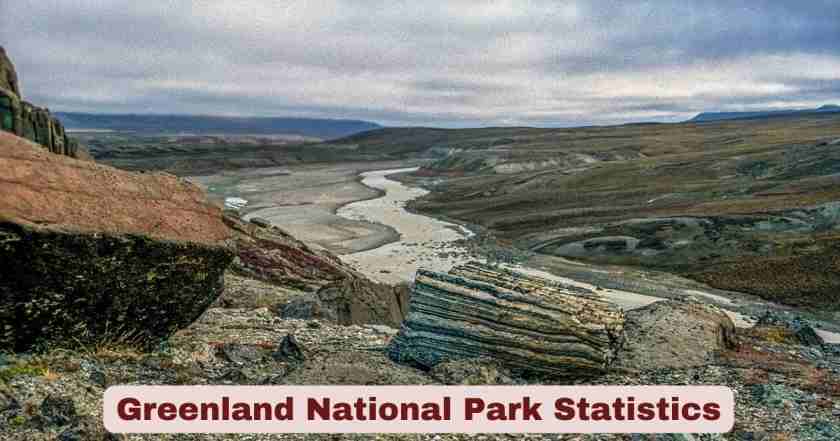

Northeast Greenland National Park stands as an extraordinary testament to Arctic wilderness preservation, holding the distinction of being the world’s largest national park. Covering an immense 972,000 square kilometers, this protected area surpasses 166 of the world’s 195 countries in size and represents one of Earth’s last remaining truly pristine wilderness regions. The park’s significance extends beyond its remarkable dimensions, serving as a critical habitat for Arctic wildlife and a living laboratory for understanding climate change impacts in polar regions.

The year 2026 marks a pivotal moment for Northeast Greenland National Park, driven primarily by the total solar eclipse occurring on August 12, 2026, which will traverse directly through the park’s territory. This rare celestial event has catalyzed unprecedented tourism interest, with expedition cruise companies organizing specialized voyages to position visitors along the eclipse’s centerline. The surge in accessibility follows the opening of Nuuk’s new international airport in November 2024 and the launch of direct flights from North America in June 2025, fundamentally transforming how travelers can reach Greenland and its remote national treasure.

Interesting Facts and Latest Statistics for Greenland National Park 2026

| Key Facts About Greenland National Park in 2026 | Statistics |

|---|---|

| Total Area of Northeast Greenland National Park | 972,000 square kilometers (375,000 square miles) |

| Year Established | 1974 |

| Year Expanded to Current Size | 1988 |

| Percentage of Park Covered by Greenland Ice Sheet | 80% |

| Permanent Human Population | 0 residents |

| Seasonal Personnel (Weather and Military Stations) | 40 people approximately |

| Number of Sites with Regular Summertime Use | 400 sites |

| Estimated Musk Oxen Population | 5,000 to 15,000 animals |

| Percentage of World Musk Oxen Population (1993 Estimate) | 40% |

| Named Mountain Peaks in Park | 126 peaks |

| Tallest Peak (Winston Bjerg) | 2,002 meters (6,568 feet) |

| Closest Settlement (Ittoqqortoormiit) Population | 363 inhabitants (2024 estimate) |

| Solar Eclipse Date | August 12, 2026 |

| Totality Duration at Centerline | 2 minutes 17 seconds |

Data Source: Government of Greenland Ministry of Environment and Nature, Visit Greenland, UNESCO Biosphere Reserve Programme, Danish Armed Forces Sirius Patrol, 2024-2026

These statistics reveal the extraordinary scale and ecological significance of Northeast Greenland National Park. At 972,000 square kilometers, the park is larger than countries including Tanzania, Egypt, and Nigeria, and equals roughly 100 times the size of Yellowstone National Park in the United States. The fact that 80% remains permanently covered by the Greenland Ice Sheet underscores the extreme Arctic conditions, yet the ice-free coastal regions support thriving ecosystems.

The complete absence of permanent human residents distinguishes this park from virtually all other protected areas worldwide. The 40 seasonal personnel stationed at weather monitoring stations and military outposts represent the only year-round human presence, primarily members of the elite Sirius Dog Sled Patrol who conduct sovereignty patrols using traditional dog sledding methods. The estimated 5,000 to 15,000 musk oxen represent one of the largest populations of these Ice Age survivors anywhere on Earth, with the 1993 assessment indicating the park hosted 40% of the world’s total musk oxen population. The August 12, 2026 total solar eclipse with 2 minutes 17 seconds of totality represents the longest duration observable anywhere along the entire eclipse path, making Greenland’s remote fjords the optimal viewing location globally.

Size and Geographic Comparisons of Greenland National Park 2026

| Comparison Category | Northeast Greenland National Park | Comparative Example |

|---|---|---|

| Total Area | 972,000 square kilometers | Larger than Tanzania (945,087 km²) |

| Area in Square Miles | 375,000 square miles | Approximately 4 times the size of United Kingdom |

| Comparison to US National Parks | 100 times larger than Yellowstone | Yellowstone is 8,991 km² |

| Countries Smaller Than the Park | 166 countries | Out of 195 total countries worldwide |

| Ranking Among Protected Areas | 10th largest protected area | Largest land-based protected area |

| Latitude Range | 74°30′ to 81°36′ North | Extends into High Arctic |

| Coastline Length | Several thousand kilometers | Along Greenland Sea |

| Ice-Free Area | Approximately 194,400 km² (20%) | Equivalent to entire Senegal |

Data Source: Government of Greenland Environmental Department, GRID-Arendal, United Nations Environment Programme, UNESCO, 2024-2026

The sheer magnitude of Northeast Greenland National Park defies easy comprehension. At 972,000 square kilometers, this single protected area encompasses more territory than 166 of the world’s 195 countries, making it larger than nations including Egypt, Venezuela, and Pakistan. The comparison to Yellowstone National Park, America’s iconic first national park, puts this in perspective: Northeast Greenland National Park is 100 times larger, demonstrating the unprecedented scale of Arctic wilderness protection.

The park’s position as the 10th largest protected area globally becomes even more impressive when considering that the nine larger protected areas consist predominantly of ocean waters rather than land. This makes Northeast Greenland National Park effectively the world’s largest land-based protected wilderness. The 20% ice-free coastal areas totaling approximately 194,400 square kilometers still represent an enormous territory roughly equivalent to the entire nation of Senegal, providing extensive habitat for Arctic wildlife despite the overwhelming ice coverage. The latitude range from 74°30′ to 81°36′ North places the park firmly within High Arctic ecosystems, with the northern reaches experiencing four months of continuous polar night during winter and corresponding months of midnight sun during summer.

Wildlife Populations in Greenland National Park 2026

| Species | Estimated Population/Status | Conservation Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Musk Oxen | 5,000 to 15,000 individuals | 40% of world population (1993 baseline) |

| Polar Bears | Part of East Greenland subpopulation | Prime habitat with stable sea ice |

| Arctic Wolves | Small but important population | Rare Greenland wolf subspecies |

| Arctic Foxes | Healthy population | Year-round residents |

| Arctic Hares | Widespread | Primary prey species |

| Collared Lemmings | Widespread | Key to tundra food web |

| Walruses | Numerous along coast | Breeding and haul-out sites |

| Ringed Seals | Abundant in coastal waters | Primary polar bear prey |

| Bearded Seals | Common in fjords | Important marine mammal |

| Narwhals | Migratory population | Use fjords seasonally |

| Beluga Whales | Migratory population | Summer feeding grounds |

| Breeding Bird Species | Approximately 60 species | Only 2 year-round (ravens, ptarmigans) |

Data Source: Government of Greenland Wildlife Monitoring, Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, Northeast Greenland National Park Management, 2024-2026

Northeast Greenland National Park supports exceptional Arctic wildlife populations despite the harsh climate and extensive ice coverage. The 5,000 to 15,000 musk oxen represent one of the most significant concentrations of these prehistoric Ice Age survivors anywhere on Earth. The 1993 scientific assessment that found 40% of the world’s musk oxen population resided in the park established its global importance for this species, which survived the Pleistocene extinction that eliminated most other megafauna.

The park provides prime polar bear habitat, particularly along the extensive coastline where stable sea ice persists much of the year, creating ideal hunting platforms for seals. The East Greenland polar bear subpopulation benefits from the park’s protected status and minimal human disturbance. The Greenland wolf, a rare subspecies of gray wolf found only in Greenland and northern Canada, maintains a small but viable population within the park. Unlike most wolf populations that form large packs, these Arctic-adapted wolves typically travel alone or in pairs due to the scattered distribution of prey. The marine ecosystem supports abundant ringed seals, bearded seals, harp seals, and hooded seals, which in turn sustain polar bear populations. Migratory cetaceans including narwhals and beluga whales utilize the park’s deep fjords during summer months, while approximately 60 bird species breed in the park during the brief Arctic summer, though only 2 species—ravens and ptarmigans—remain year-round in this extreme environment.

Tourism and Accessibility to Greenland National Park in 2026

| Access and Tourism Metric | Details for 2026 |

|---|---|

| Permit Requirement | Mandatory government permit required 12+ weeks advance |

| Permanent Accommodations | None available |

| Commercial Accommodation | Zero hotels or lodges |

| Camping Policy | Allowed with restrictions near wildlife sites |

| Primary Access Method | Expedition cruise ships |

| Secondary Access Method | Private charter flights to Constable Point |

| Closest Airport | Nerlerit Inaat (50 miles/80 km from southern border) |

| Closest Settlement | Ittoqqortoormiit (363 residents) |

| Estimated Annual Visitors (Pre-2026) | Few hundred visitors |

| Projected 2026 Eclipse Visitors | Several thousand (via expedition cruises) |

| Average Expedition Cruise Length | 12-14 days |

| Peak Visit Season | July-August |

Data Source: Government of Greenland Ministry of Science and Environment, Visit Greenland, Northeast Greenland National Park Administration, 2024-2026

Access to Northeast Greenland National Park remains highly restricted and logistically challenging, preserving its wilderness character while limiting environmental impacts. Every visitor must obtain a government permit at least 12 weeks in advance, submitting detailed plans including itinerary, safety equipment, participant qualifications, and environmental protection measures. The complete absence of commercial accommodations—no hotels, lodges, or permanent campgrounds—means visitors must be entirely self-sufficient or travel via expedition cruise vessels.

Expedition cruises represent the primary access method, typically departing from Iceland or Svalbard and spending 12-14 days exploring Greenland’s east coast including sections of the national park. These voyages historically attracted only a few hundred adventurous travelers annually, making the park one of Earth’s least-visited protected areas. However, 2026 represents an extraordinary exception due to the August 12 total solar eclipse, with dozens of specialized eclipse cruises expected to bring several thousand visitors to witness totality from the park’s fjords. The Nerlerit Inaat airport located 50 miles (80 kilometers) from the park’s southern boundary serves as the access point for air travelers, connecting to Ittoqqortoormiit, though most visitors arrive by ship. The remote settlement of Ittoqqortoormiit with just 363 residents represents the nearest human community, offering a glimpse of life in one of Earth’s most isolated places before entering the completely uninhabited park wilderness.

August 12, 2026 Total Solar Eclipse Event in Greenland National Park

| Eclipse Specifications | Details |

|---|---|

| Eclipse Date | August 12, 2026 |

| Eclipse Type | Total Solar Eclipse |

| Time of First Contact (Partial Eclipse Begins) | 16:37 local time |

| Time of Totality Begins | 17:37 local time |

| Duration of Totality | 2 minutes 17 seconds |

| Time Diamond Ring Effect (Totality Ends) | 17:40 local time |

| Time of Last Contact (Eclipse Ends) | 18:33 local time |

| Total Eclipse Experience Duration | Approximately 2 hours |

| Moon’s Shadow Speed | 4,000 kilometers per hour |

| Optimal Viewing Location | Scoresby Sund (Scoresbysund) fjord system |

| Cloud Cover Probability | 45-50% in deep fjords (favorable) |

| Satellite-Measured Clear Sky Probability | Better than 70% chance in Scoresby Sund |

| Previous Total Eclipse in Arctic Circle | 2015 |

| Next Total Eclipse in Arctic | Unknown future date |

Data Source: NASA Eclipse Path Data, Eclipsophile Meteorological Analysis, Government of Greenland Tourism Authority, Expedition Cruise Operators, 2025-2026

The August 12, 2026 total solar eclipse represents a once-in-a-generation celestial event for Northeast Greenland National Park and has catalyzed unprecedented tourism interest in this remote wilderness. The moon’s shadow will track southward through mountainous Northeast Greenland before reaching the dramatic Blosseville Coast at 16:37 local time, beginning the partial eclipse phase. Totality will commence at 17:37 with the sun positioned in the southwestern sky, plunging the landscape into darkness for 2 minutes and 17 seconds—the longest totality duration observable anywhere along the entire eclipse path.

Scoresby Sund, the world’s largest fjord system, represents the optimal viewing location due to a meteorological phenomenon unique to Greenland’s geography. As cold, dry air flows down from the massive Greenland Ice Sheet into the deep fjords, it warms and dries further through compression, creating a microclimate with significantly lower cloud cover than surrounding regions. Satellite observations from past Augusts show cloud cover in the deepest reaches of Scoresby Sund averages just 45-50%, compared to 65% near the fjord entrance at Ittoqqortoormiit. Statistical analysis indicates a better than 70% chance of clear skies during the eclipse, making this one of the most favorable viewing locations along the path that otherwise crosses predominantly cloudy Arctic Ocean regions. The moon’s shadow will race across Greenland at 4,000 kilometers per hour, passing just 100 kilometers south of the North Pole before reaching the park. The 2026 eclipse holds special significance as the previous total solar eclipse north of the Arctic Circle occurred in 2015, making such events exceptionally rare in polar regions where the sun only illuminates each pole for part of the year.

Climate and Environmental Conditions in Greenland National Park 2026

| Climate Metric | Measurements |

|---|---|

| Climate Classification | Polar Tundra (Köppen: ET) |

| Average Annual Temperature (Coastline) | -5°C to -15°C (-10°C to -20°C interior) |

| Winter Average Temperature | -20°C (November-April) |

| Summer Average Temperature | 10°C to 15°C (June-August) |

| Annual Precipitation | 100-200 mm (Arctic desert designation) |

| Polar Night Duration (Northern Reaches) | Up to 4 months |

| Midnight Sun Duration | Corresponding summer months |

| Extreme Wind Events (Piteraq) | Up to 200 km/h katabatic winds |

| Vegetation Coverage (Coastal Areas) | 33% lichens and mosses, 3% herbaceous plants |

| Vegetation Increase Since 1990s | Up to 22.5% greening trend |

| Active Layer Thaw Depth (Permafrost) | Increasing due to climate change |

Data Source: Greenland Meteorological Institute, University of Copenhagen Climate Research, Northeast Greenland National Park Environmental Monitoring, 2024-2026

Northeast Greenland National Park experiences extreme polar climate conditions that shape all aspects of its ecosystem. Classified as polar tundra (Köppen climate designation ET), the park receives so little precipitation—just 100-200 millimeters annually—that it qualifies as an Arctic desert, one of the driest regions on Earth. Coastal areas benefit from slight maritime moderation, averaging -5°C to -15°C annually, while the interior ice-covered regions remain colder at -15°C to -25°C throughout the year.

The seasonal temperature swing creates dramatic contrasts: winter temperatures averaging -20°C from November through April give way to relatively mild summer temperatures of 10-15°C during the brief June-August period when the midnight sun bathes the landscape in continuous daylight. The northern sections experience four months of polar night when the sun never rises, followed by corresponding months when it never sets. Katabatic winds known as piteraq represent one of the park’s most dangerous weather phenomena, accelerating down the steep ice sheet slopes to reach speeds exceeding 200 kilometers per hour, creating whiteout conditions and extreme wind chill. Recent climate monitoring reveals significant greening trends, with vegetation coverage increasing by up to 22.5% since the 1990s in areas with adequate moisture. This expansion of shrub cover, particularly Salix arctica (Arctic willow), reflects warming temperatures but raises concerns about altered ecosystem dynamics. Permafrost thawing has accelerated, with increasing active layer depths and longer thaw periods documented by research stations, representing a critical indicator of Arctic climate change impacts within the park.

Sirius Dog Sled Patrol Operations in Greenland National Park 2026

| Sirius Patrol Specification | Details |

|---|---|

| Official Name | Sirius Dog Sled Patrol (Siriuspatruljen) |

| Military Affiliation | Elite unit of Danish Naval Forces |

| Primary Mission | Sovereignty enforcement and park monitoring |

| Area of Responsibility | Entire Northeast Greenland National Park coastline |

| Patrol Method (Winter) | Traditional dog sled teams |

| Patrol Method (Summer) | Boat patrols |

| Approximate Personnel | 12-15 patrol members |

| Typical Patrol Duration | 4-month winter expeditions |

| Total Annual Patrol Distance | Up to 30,000 kilometers combined |

| Number of Sled Dogs | Approximately 100-110 dogs |

| Patrol Huts Maintained | Multiple historic huts including Varghytta (1929) |

| Weather Station Monitoring | Regular visits to remote stations |

| Notable Historic Missions | Continuous operations since 1950 |

Data Source: Danish Defence Command, Sirius Patrol Official Records, Northeast Greenland National Park Administration, Arctic Council Reports, 2024-2026

The Sirius Dog Sled Patrol represents one of the world’s most unique military units, conducting year-round sovereignty patrols and environmental monitoring across Northeast Greenland National Park’s vast territory. Established in 1950, this elite Danish naval unit maintains Denmark’s (and by extension Greenland’s) presence in this otherwise uninhabited wilderness, enforcing regulations, monitoring environmental conditions, and providing search and rescue capabilities in emergencies.

The patrol’s winter operations rely entirely on traditional methods: teams of 12-15 specially trained personnel traverse the frozen coastline using dog sled teams, covering enormous distances in some of Earth’s harshest conditions. Four-month winter expeditions see patrol members and their dogs covering sections of the park’s coastline, with the entire unit collectively traveling up to 30,000 kilometers annually. The patrol maintains approximately 100-110 highly trained Greenland sled dogs, descendants of ancient Inuit working dog lines specially adapted for Arctic conditions. These dogs can haul heavy loads across sea ice, broken terrain, and steep mountain passes where no motorized vehicle could operate. During summer months when ice conditions become too dangerous for sledding, the patrol switches to boat patrols of the coastal waters. The team maintains and regularly visits multiple historic patrol huts scattered throughout the park, including Varghytta (“the wolf hut”) built in 1929 and still in active use. Patrol members undergo extensive Arctic survival training and typically serve two-year postings, gaining intimate knowledge of the park’s geography, wildlife, weather patterns, and environmental changes, making them among the world’s foremost experts on High Arctic wilderness conditions.

Historical and Cultural Heritage in Greenland National Park 2026

| Cultural Heritage Element | Details |

|---|---|

| Paleo-Inuit Cultures | Independence I and Dorset cultures (2,400-200 BC) |

| Neo-Inuit Cultures | Thule Culture (1300-1850 AD) |

| Archaeological Preservation | Extremely well-preserved due to cold climate |

| Visible Archaeological Features | Tent rings, stone tools, turf houses |

| Trapper Era | Early 1900s to 1960s |

| Number of Remaining Trapper Huts | Over 350 structures |

| Primary Trapping Target | Arctic fox (polar fox) fur |

| Secondary Trapping Target | Occasional polar bear |

| European Market Destination | Fur exports to Europe |

| UNESCO Biosphere Reserve Designation | January 1977 |

| Research Stations (Historical) | Eismitte and North Ice (on ice sheet) |

| Mining Exploration Site | Mestersvig (cleanup completed 1986) |

Data Source: Greenland National Museum, UNESCO MAB Programme, Danish Polar Center, Archaeological Survey of Greenland, 2024-2026

Despite its current status as uninhabited wilderness, Northeast Greenland National Park contains extensive evidence of human occupation spanning thousands of years. Paleo-Inuit cultures including Independence I (approximately 2,400 BC) and Dorset peoples (ending around 200 BC) established seasonal camps throughout the coastal areas, hunting musk oxen, seals, and other wildlife. The Neo-Inuit Thule Culture (1300-1850 AD) later inhabited the region, leaving behind numerous archaeological sites.

The Arctic climate’s extreme cold creates exceptional preservation conditions, with tent rings (circles of stones used to anchor tent edges), stone tools, and turf house remains lying openly exposed on the surface rather than buried, appearing remarkably fresh despite being hundreds or thousands of years old. The more recent trapper era from the early 1900s through the 1960s saw European hunters establish seasonal camps throughout the park, constructing over 350 small huts that provided shelter during winter fur trapping expeditions. These trappers targeted primarily Arctic fox pelts destined for European fashion markets, with occasional polar bear hunting supplementing their income. The last trappers departed by the 1960s as fur demand declined and conservation concerns grew. The park received UNESCO Biosphere Reserve designation in January 1977, recognizing its global ecological significance. Historical research camps on the Greenland Ice Sheet, including the famous Eismitte station (German for “Mid-Ice”) and North Ice, fall within the park’s boundaries and played crucial roles in early glaciology and meteorology studies. The Mestersvig mining exploration site near the coast operated until 1986, when the final 40 residents departed after completing cleanup operations, marking the end of the last permanent human habitation within the park’s boundaries.

Greenland Tourism Growth and Infrastructure Development 2024-2026

| Tourism Development Metric | Statistic |

|---|---|

| Nuuk International Airport Opening | November 2024 |

| United Airlines Direct Flight Launch | June 14, 2025 (New York to Nuuk) |

| Icelandair Partnership Seat Capacity Increase | 120% increase |

| Tourism Contribution to Greenland GDP (2024) | 4.9% (1.245 billion DKK in value) |

| Tourism Employment (2024) | 1,800 direct jobs (6.2% of all jobs) |

| Tourist Expenditure (2024) | 3 billion DKK total |

| International Tourist Spending (2024) | 1.7 billion DKK (58% of total) |

| Domestic Tourist Spending (2024) | 1.2 billion DKK (42% of total) |

| Projected US Visitor Increase (2025-2026) | May double from 2024 levels |

| Peak Season Available Seats (2025) | 105,000 seats (April-August) |

| Peak Season Available Seats (2023) | 55,000 seats (April-August) |

| Visitor Numbers Pre-Pandemic (2019) | 105,000 total visitors |

| Visitor Numbers Pandemic (2020) | Approximately 77,000 visitors |

Data Source: Visit Greenland Tourism Satellite Account, Statistics Greenland, Greenland Airports, Air Greenland, United Airlines, 2024-2026

Greenland’s tourism industry entered a transformative period during 2024-2026, driven by major infrastructure investments and growing international interest. The opening of Nuuk’s new international airport in November 2024 represents a watershed moment, enabling direct long-haul flights from North America and Europe for the first time. Previously, nearly all international visitors required connections through Iceland or Denmark, adding significant time and expense to journeys. The June 14, 2025 launch of United Airlines’ direct New York to Nuuk service immediately opened Greenland to the lucrative North American market, with projections suggesting US visitor numbers may double compared to 2024.

Tourism’s economic impact in 2024 reached 1.245 billion Danish kroner, representing 4.9% of Greenland’s GDP and supporting 1,800 direct jobs (6.2% of total employment). Total tourist expenditure hit 3 billion DKK, split between 1.7 billion from international visitors (58%) and 1.2 billion from domestic travelers (42%). International tourists spend heavily on flights (31% of expenses), experiences/activities (14%), and accommodation/food (21%). The Icelandair partnership renewal delivered a 120% increase in seat capacity, while total peak season availability jumped from 55,000 seats in 2023 to 105,000 seats in 2025 (April through August), nearly doubling access. Greenland experienced strong tourism growth from 77,000 visitors in 2015 to 105,000 in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic temporarily disrupted the industry. The 2026 total solar eclipse is expected to accelerate recovery beyond pre-pandemic levels, though Greenland authorities emphasize “value-creating tourism” that prioritizes quality, longer stays, and meaningful cultural engagement over simply maximizing visitor numbers, learning from overtourism challenges faced by destinations like Iceland.

Climate Change Impacts in Greenland National Park 2024-2026

| Climate Change Indicator | Observed Trend |

|---|---|

| Vegetation Increase Since 1990s | Up to 22.5% greening in parts of Northeast Greenland |

| Arctic Willow (Salix arctica) Expansion | Expanded shrub cover documented via satellite |

| Permafrost Active Layer Depth | Increasing depths |

| Permafrost Thaw Period Duration | Longer annual thaw periods |

| Sea Ice Retreat Projections (2025) | Potential 25%+ increase in marine productivity |

| Plankton and Fish Stock Projections | Potential increases from enhanced productivity |

| Arctic Warming Rate | Accelerated compared to global average |

| Glacier Movement Rate | Northeast Greenland Ice Stream (NEGIS) accelerating |

| Coastal Glacier Calving Frequency | Increased at Gully, Sefstrøm, Hamberg glaciers |

| Biodiversity Concerns | Greening may reduce diversity despite productivity gains |

| Food Web Alterations | Shifting species composition and timing |

| Shipping Traffic Pollution Risk | Increasing with ice retreat |

Data Source: Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, University of Copenhagen Arctic Research Center, Danish Meteorological Institute, Northeast Greenland National Park Environmental Monitoring Programme, 2024-2026

Climate change impacts manifest dramatically throughout Northeast Greenland National Park, with 2024-2026 observations documenting accelerating environmental transformations. The most visible change involves vegetation expansion, with studies revealing up to 22.5% increases in plant coverage since the 1990s in parts of Northeast Greenland, though regional variation depends heavily on moisture availability. Arctic willow (Salix arctica) has expanded its shrub cover significantly, documented through both satellite imagery analysis and field surveys, creating taller, denser vegetation where previously only low-growing tundra plants survived.

Permafrost degradation represents a critical indicator, with active layer depths (the surface layer that thaws seasonally) increasing steadily and thaw periods extending longer each summer. This permafrost change affects hydrology, vegetation patterns, wildlife habitat, and even the stability of archaeological remains that have been frozen for millennia. Marine ecosystem projections suggest that sea ice retreat in Northeast Greenland could enhance productivity by more than 25%, potentially increasing plankton abundance and fish stocks that underpin the entire marine food web. However, this apparent benefit carries complex trade-offs: while short-term productivity may increase, the fundamental transformation of Arctic ecosystems threatens biodiversity, with concerns that expanding shrub cover could actually reduce overall biodiversity despite increased biomass. Glacier dynamics show the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream (NEGIS) accelerating its flow toward the ocean, while coastal glaciers including The Gully, Sefstrøm, and Hamberg exhibit increased calving frequency, contributing to sea level rise. Shipping traffic increases accompanying ice retreat introduce new pollution risks including potential oil spills and contaminant introduction in previously pristine waters. Park management coordinates with international research partners to track these ecological indicators and adapt conservation strategies, recognizing that Northeast Greenland National Park functions as a critical sentinel for understanding Arctic climate change impacts globally.

Protected Area Management and Conservation Priorities in Greenland National Park 2026

| Management Element | Details |

|---|---|

| Administering Authority | Government of Greenland Department of Environment and Nature |

| UNESCO Designation | Biosphere Reserve (January 1977) |

| Resource Extraction Policy | Banned to prevent habitat disruption |

| Monitoring Programs | Climate change effects, permafrost, species migration |

| Hunting Permissions | Limited subsistence hunting by Ittoqqortoormiit residents |

| Scientific Research Stations | Multiple weather and environmental monitoring stations |

| Visitor Permit Processing Time | Minimum 12 weeks advance application |

| Camping Restrictions | Prohibited near wildlife breeding/resting sites |

| Major Conservation Threats | Arctic warming, shipping pollution, habitat loss |

| International Collaboration | Arctic Council, UNESCO MAB, climate research partnerships |

| Polar Bear Protected Area | New protected area established 2023 |

| Ecological Monitoring Focus | Greening trends, biodiversity, food web shifts |

Data Source: Government of Greenland Ministry of Environment and Nature, UNESCO Man and Biosphere Programme, Arctic Council Conservation Working Group, 2024-2026

Northeast Greenland National Park operates under management by the Government of Greenland’s Department of Environment and Nature, which coordinates conservation priorities, research permits, visitor access, and environmental monitoring. The park’s UNESCO Biosphere Reserve designation (January 1977) recognizes its global ecological significance and commits management to balancing conservation with limited sustainable human uses and scientific research.

Resource extraction remains strictly banned, preventing mining, oil and gas development, and commercial resource harvest that would disrupt the pristine environment. This prohibition reflects the park’s primary mission of wilderness preservation and ecological protection rather than economic exploitation. Limited subsistence hunting is permitted for residents of Ittoqqortoormiit, acknowledging traditional indigenous relationships with the land while maintaining sustainable harvest levels that don’t threaten wildlife populations. Major conservation priorities focus on monitoring and mitigating climate change impacts, including accelerated Arctic warming causing habitat loss through ice melt and vegetation changes. The documented greening trends with expanded shrub cover raise concerns about reduced biodiversity and altered food webs despite apparent productivity increases.

Disclaimer: This research report is compiled from publicly available sources. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is given as to the completeness or reliability of the information. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions, losses, or damages of any kind arising from the use of this report.